#20: The Nine Stages of the Decomposition of a Corpse

Earlier she had watched the

festival procession as it passed

by her house. Some of the par-

ticipants carried lanterns, others

fat balloons that were tethered

to a holding stick. If the balloons

had feelings she knew how they

would feel. Bloating she had

experienced many times before -

at menstruation time, or eating

something that did not agree

with her. She had it now, but this

seemed different, more intense.

Carried with it a sense of dread.

How should we treat the newly dead?

Are there possible signs of life?

Should we try to revive?

Who can make the determination?

Are we sure that this is who we think it is?

What do we say has happened?

Was the death natural or suspicious?

What was the official time of death?

Who can make the pronouncement?

What should they say?

Confirmation that death has occurred?

Or verification that life is extinct?

Who should they tell?

Is it possible to preserve the body?

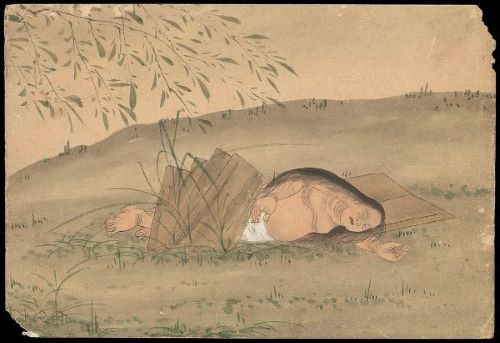

Without treatment, the body swells

with gas, the skin discolors, pores

begin to leak rotting flesh, & that

then followed by blood. Elsewhere

there are weeping trees. In sympathy?

Or something else? The catacombs

are no place for writing poetry. Get

out into the sun, sit on a stone bench,

or find a swing to exercise on. Delibe-

rate movement is much better than the

accidental discovery of the self in passage

to the afterlife, hung from a tree, or lying

swollen & gaseous on the grass. Memory's

composition will likely be decomposition.

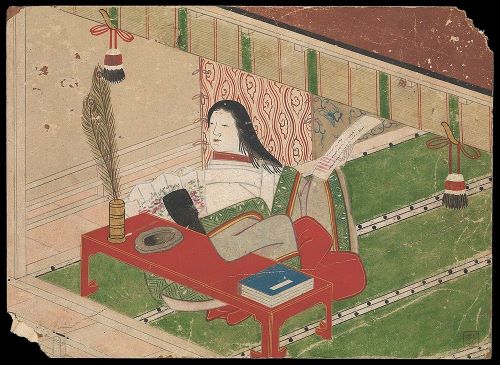

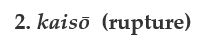

A note on the paintings. These are the first three in a sequence of nine called Kusōzu: the death of a noble lady and the decay of her body, painted c. 1700. Watercolors. They are part of the Wellcome Collection. Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0).

The prompt for these poems is a list poem by Tom Beckett, "One Hundred Titles," which was published in Otoliths in February, 2022.